This article originally appeared in Sea History.

In 1926, the Hispanic American Historical Review reappeared after a four-year hiatus. Founded in 1916 to focus on Latin American scholarship, it lost its financial backing in 1922 and lay dormant until picked up by Duke University Press years later. Newly confident and secure in their jobs, the journal’s editors offered a poem to leaven their comeback issue’s staid articles, book reviews, and bibliographic notices. “It has not been the policy of the Review to publish metrical matter,” they explained in a brief note. Nonetheless, they believed the poem, titled “The Archives of the Indies at Seville,” by Irene A. Wright, an American researcher living in Spain, was “so true to the spirit” of that remarkable institution that it deserved attention. The selection occupied pride of place at the journal’s front and consisted of five vigorous stanzas that bowled along like a caravel driven by the trades. “These are the Archives of the Indies!” Wright began.

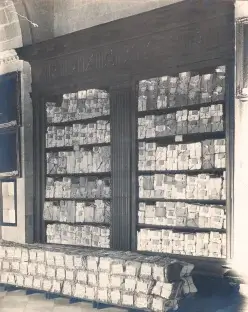

Here—in these tall cases, built from the marble floor Toward domed, arched ceiling—

Here are stored, in blue-wrapped bundles, pack on pack, The papers passed between old Spain and her far colonies.

In excited cadences, Wright revealed the world of action and adventure those papers contained.

Here—the voice of guns!

Hawkins’ and Drake’s and doughty Baskerville’s!

Pater’s and Heyn’s! …

How they sail yet on this troubled sea

Of finite History!

How brave they sail!

How brave they sail through these old papers here preserved!

These are the Archives of the Indies! These! … Who reads these records through hears arrows whistle, feels the whir

Of good Toledo steel; sees Indians skulk,

Creeping at dawn to storm the palisades

Of unremembered posts on river routes and shores: “My Governor, send help! We are surrounded.” …

And she acknowledged the “bold friar, acting courier” by whom the records were carried and saved, within them a message that “rings down the centuries.” On Wright con-tinued, listing exotic wonders like Aztec shrines, Inca pal-aces, stately galleons, and plundering pirates before finally ending with a flourish:

These are the Archives of the Indies! These—Ashes of empire!

Worthless! Bale on bale

So much old paper—tied with dirty string!

Wright was no stranger to the Review’s editors and readers. Indeed, she had published more than half a dozen articles with them previously, mostly about early Cuban and Jamaican history. She also engaged in research for prominent historians like J. Franklin Jameson, editor of the American Historical Review and a founder of the Hispanic American Historical Review. Jameson affectionately described her in a letter to a colleague as a demon for work, full of enterprise and energy, and yet amiable and kind, nowise overwhelming or obstreperous. She is a character, breezy and in-formal, not like anybody else, but thoroughly like-able and full of kindness toward everyone.

Ursula Lamb, a young German-American historian, held her in awe. “Irene Wright was a tall statuesque presence,” she recalled decades later, “built to be seen from a distance and aware of it.”

When Wright’s poem appeared in the Review, she had a formidable reputation as a researcher and translator specializing in Spain’s New World history of conquest and colonization. She was thoroughly familiar with the Seville archives, commonly known as the AGI (Archivos General de Indias), which was home to virtually all the official documents relating to that history, and she could decipher centuries-old penmanship, whether flowery or scribbled. “We of the United States,” she later remarked, “seldom realize how much of our own early history lies in those early reports of Spanish soldiers, traders, and priests. Their records are as much our history as Spain’s.” To demonstrate her point graphically, she joked that in the AGI, “I found Peter Stuyvesant’s lost leg. Well, perhaps not precisely the actual limb of that famous peg-legged Governor of New Amsterdam, but I was able to establish for the first time that he lost it in his siege of the Leeward Island of San Martin.” Jameson declared, “She knows the archives of the Indies, so far as the materials for American history are concerned, better than anyone else does or ever has.”

When Wright returned to the United States in 1936, on the eve of the Spanish Civil War, her accomplishments included editing and translating thousands of documents for institutions like the Florida State Historical Society, the Library of Congress, the Hakluyt Society, and the governments of Great Britain, Spain, and the Netherlands. Her literary corpus included over a dozen articles and ten books, and she was recognized with numerous awards and honors. James Alexander Williamson, a British maritime historian and vice president of the Hakluyt Society, credited her with cracking open the Spanish side of the Elizabethan Age’s Caribbean conflicts. “Our debt to Miss Wright’s research and editing is not easy to express,” he concluded.

Irene Aloha Wright’s path to such prominence was by no means direct. Born in Ouray, Colorado, 19 December 1879, she grew up among Irish immigrants. The origin of her unusual middle name is unknown, but perhaps it was her father Edward’s idea. He owned part interest in a gold mine, and in 1888 he built an opera house downtown, so he must have had a bit of the theatrical about him. After he died during Irene’s 15th year, her mother, Letitia, sent her to a girl’s school in Roanoke, Virginia, where it did not take long for the youngster’s independent spirit to manifest itself. Bored by the routine, she skipped her second year and hopped on a train to Mexico with $300 worth of gold sewn into her dress. “It seemed to me, definitely, that Mexico City would be a great deal more fun than Virginia,” she later laughed.

And so it was. Wright mastered Spanish and went to work teaching English, translating museum guidebooks, and serving as a governess for the country’s vice president. The latter experience proved especially useful, acquainting young Wright with the traditions of upper-class Latin Catholic life. That provided, certainly, one form of education, but after three years Wright decided she needed more formal schooling and returned to finish at Roanoke, doubtless to Letitia’s great relief. She subsequently attended Stanford University and graduated in 1904 with a bachelor’s degree in history.

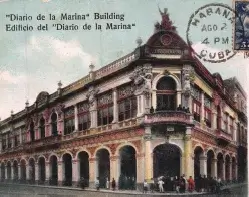

Women faced very limited professional opportunities during the early 1900s. Rather than marrying and settling into a domestic routine, Wright chose adventure and again traveled south, along with her mother, her “constant, patient, tireless companion,” for a newspaper job at the Havana Post. In her eloquent 1910 memoir, Cuba, Wright described steaming into Havana Harbor before dawn. She and her mother were on deck when they sighted Morro lighthouse’s bright beacon. “Then, gradually, details of a picture detached themselves from a gray background,” she wrote. “We made out the outlines of Morro. We saw minor lights, those of the barracks on the sloping shore to the left of it, and those, more numerous, of the city itself, across the channel, at the right.” The sky brightened further, the sun rose, and before them lay such a city “as I had not supposed ever existed off the black curtain of a stage set for a light opera.” The bay shore curved before them in “gracious welcome,” and over it all “lay the most delicate, shifting, blue-gray mist, which made what our eyes beheld seem the more unreal. I felt that we had arrived in an enchanted land.”

Wright never lost that sense of enchantment, though the discomforts and frustrations of living in a newly independent tropical nation occasionally challenged it. In the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, Cuba shed its Spanish yoke, but thanks to the Platt Amendment (1901), the United States reserved the right to unilaterally intervene in its affairs and to lease land for a military base at Guantánamo. For herself, Wright dubbed the island “the land of topsy-turvy.” She continued: “Here logic and rational sequence are not the rule.” Life seemed more like a play, and “contradiction exists in all the details.” Inconsistently enforced rules, endemic corruption, confusing business practices, and rampant bureaucracy all prevailed. Racial complexity wove through every social class, resulting in more nuanced interpersonal relations than in the United States. “Here, black is not necessarily black,” Wright explained, “but may carry a legal document to prove its color white; white is not surely white but may only ‘pass’ for such.” Wright admitted that she came to Cuba “with every prejudice we Americans are accustomed to entertain against blacks, and especially against mixed breeds; to me, then, a single drop of black blood was worse than a whole bucketful.” To her credit, Cuba compelled her to relax these views and take the country and its people as she found them, with only the occasional grumble.

More difficult was the climate. The heat and humidity were insufferable, and simply crossing the Plaza de Armas seemed like an endurance contest thanks to “the glare from its paths, which penetrates the eyes like a white-hot knife.” During the long summers, hurricanes posed a serious threat. Wright recalled that she had “the rare luck to be outdoors in the storm of 1906. I shall not forget to my dying day, how the wind howled up and down the narrow streets, how the rain twisted and whirled, driven by winds that blew from every quarter at one and the same time.”

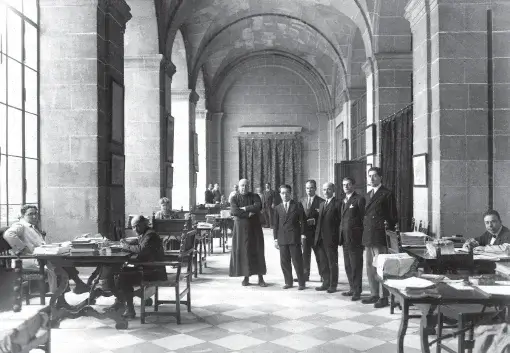

Not surprisingly, given her large-mindedness and go-ahead nature, Wright flourished professionally. After two years at the Post, she worked as city editor for the Havana Telegraph. In 1908 she bought and edited The Cuba Magazine, an English language weekly. She also did a stint at the island’s most distinguished newspaper, Havana’s Diario de la Marina. Wright reveled in the Diario’s elegant offices, “tiled, painted, decorated with chandeliers, statuettes, artificial flowers, and portraits,” where everyone dressed to the nines and management forbade scattering papers on “the sanctum floor.” Predictably, Wright ignored this diktat until the editor issued her a stern rebuke. The presence of this confident, unmarried American woman proved en-tirely novel to the paper’s male employees. There were a few early complaints, namely that Wright “walked like a man, looked neither to right nor to left, and favored them with no ‘silvery cachinnations’ during office hours!” Soon, however, her colleagues grew to appreciate her work, “for they gave me a man’s title and a man’s pay, and permitted me upon occasions to assume full responsibility.” This came about even though she “moved among them as no decent woman of their own would, and they saw [her] come and go with a freedom that defied every article in their accepted code of an honest woman’s conduct.”

Throughout her time in Cuba, Wright studied the island’s history and occasionally indulged in little imaginative flights to conjure it. When crossing the heat-blasted Plaza de Armas, for example, she made herself “oblivious to the discomfort by reconstructing scenes and events which have transpired [t]here.” She wished away the Governor’s palace, “that smug yellow square which faces the Plaza from its west side,” and replaced it with “the old parish church which preceded it.” Similarly, when relaxing on the flat roof of her harborside lodgings, she fantasized about standing on the deck of a “fat caravel” surveying “a very different scene from that the physical eye beholds.” Gone were the tall buildings, packed houses, and the Morro on its headland, replaced by scattered ceiba trees, an adobe church, and cedar-built dwellings with thatched palm roofs and little gardens surrounded by rickety palings. Her reverie was rudely interrupted by a trolley car “thundering up Chacon Street,” and modern Havana flooded her senses again.

Wright’s desire to better understand Cuba’s colonial origins and social conundrums meshed perfectly with the aims of the American businessman and financier Ronald R. Conklin (best known as the inventor of the motor home). Conklin had business interests on the island and was fascinated by its past. In 1914 he financed a trip to Seville for Wright to research and write a book about the island. The so-called “Pearl of Andalusia,” Seville, Spain, is located 54 miles from the sea on the banks of the Guadalquivir River, the country’s only navigable river. Historically, the city had, of course, served as the administrative seat of Spain’s overseas empire, home to the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade), which closely regulated affairs and jealously guarded the Padrón Real (master chart). During the Age of Exploration, cartographers periodically updated this map with new information provided by far-ranging ship captains. The Crown strictly forbade its publication, lest its dissemination empower European rivals.

Seville’s glory days were long past by the time the Wrights arrived, but its wharves still bustled, and it sheltered a respectable 130,000 souls. Doubtless, mother and daughter visited the tenth-century Real Alcázar palace with its florid Moorish-influenced architecture and the famous sixteenth-century Gothic cathedral, featuring a 343-foot bell tower with the tomb of Christopher Columbus just inside its entrance. Immediately next to the cathedral stands the Archivos de Indias, a square, two-story, sixteenth-century stone building commissioned by Philip II as the Casa de Contratación headquarters and converted into an archive by Charles III in 1785. This was Irene’s destination.

Her work focused on the Papeles Procedentes de Cuba (Papers from Cuba), a massive trove of over a million pag-es gathered into 2,375 legados (bundles) and shipped from Havana to Seville during the 1880s. These papers not only concerned Cuba’s administrative history, but those of Spanish Louisiana and East and West Florida. Each legado covered a specific category—a governor’s correspondence, treasury reports, mission records, naval plans, or construction documents. Some contained only a few pages—others, hundreds. The year before Wright arrived, one observer opined that the collection presented “a virgin field for investigation.”

Wright’s first glimpse of these materials nearly overwhelmed her. Many of the bundles were neatly labeled and stored in the archives’ beautiful floor-to-ceiling wooden shelving, but others were stacked on pallets, unexamined for centuries and untouched except by the occasional mover. If she hesitated, it was but briefly. Soon she had a system in place, methodically sorting through each legado. She also hired younger scholars to assist with the translation and transcription.

Working conditions were often less than ideal. The archive had limited hours and its poorly lit work rooms were either chilly or hot, depending on the season. Staff required each research request in writing and released only one legado at a time. Despite these challenges, within two years Wright published The Early History of Cuba, 1492–1586, Written from Original Sources. In the introduction, she explained that she had abjured secondary sources because the Papeles represented a “greater wealth of material.” Nor was she shy about her achievement, declaring, “the history of the island has not been written until this present book.” An anonymous reviewer for the Southwestern Historical Quarterly was not so kind. “It seems strange that more than a year of research in the best colonial archive in Spain could not be productive of a more enlightening and sympathetic treatment of Spain’s early colonial institutions,” he mused. Nonetheless, the reviewer conceded the usefulness of an English language “connected history” of Cuba and recommended it to students.

The presence of an energetic American researcher in the AGI attracted attention, and other commissions soon followed. Among the most consequential was that of John B. Stetson Jr., son of the famed hat maker, on behalf of the Florida State Historical Society. Having recently been founded by a clutch of heritage-minded individuals, including Stetson, the Society fretted that its state’s colonial records were inaccessible to American researchers unable to afford an expensive foreign trip. Therefore, Stetson hired Wright to copy everything she could locate relating to Florida’s colonial period (broadly 1518–1821) and provided her with a photostat machine to speed the task. This was a first for the archives staff, and they marveled as this bold American woman, assisted occasionally by a frocked Spanish priest, manipulated the large camera and rolls of photographic paper. Wright worked steadily between 1924 and 1927 until Spain’s Ministry of Culture, fundamentally uncomfortable with the newfangled process, ultimately ended it. Nonetheless, Wright managed to copy more than 130,000 documents, tracing the histories of Ponce de Leon’s voyage, St. Augustine’s founding, Hernando de Soto’s murderous entrada, the Siege of Pensacola, and much more. Wright’s photostats, since microfilmed (761 rolls), form the heart of the John Batterson Stetson Collection, now at the University of Florida.

Continuing to work at fever pitch, Wright produced two books for the Hakluyt Society, Documents Concerning English Voyages to the Caribbean, 1527–1568 (1929) and Documents concerning English Voyages to the Spanish Main, 1569–1580 (1932). Each book included a detailed introduction followed by edited translations of specific documents, all copiously footnoted. A writer for the American Historical Review praised the 1527–1568 volume as “excellent” and “meticulous.” Here, for the first time for many English speakers, was the Spanish side to the epic clashes with the likes of Drake and Hawkins. “In these documents,” Wright wrote of Drake’s 1572 raid on Nombre de Dios, Panama, “we hear the English drums and trumpets sound through the Spanish town at dead of night, we see the startled residents wake to the glare of fire pikes… But here, too, we see the Spaniards rally—a dozen, two dozen—to face the enemy in the streets and break into the marketplace to make a final desperate stand there.” With his plans “gone all awry,” Drake retreated “wounded and defeated.” A two-volume set for the Dutch government followed in 1934, Nederlandsche zeevaarders op de eilanden in de Cariaïbische zee en aan de kust van Columbia en Venezuela gedurende de jaren 1621–1648 [Dutch navigators on the islands of the Caribbean Sea and on the Coast of Venezuela during the years 1621–1648.]

Wright’s 22 years at the AGI ended with the onset of the Spanish Civil War, and she returned to the United States with her mother and an adopted daughter, Flor. Relocated to Washington, DC, Wright worked as an associate archivist for the National Archives until 1938 and thereafter as a foreign affairs specialist for the Department of State, focusing on Latin American issues. Of the latter assignment, she wrote, “No small part of the purpose of the department is to keep the lamp of reason and knowledge burning amidst the blackout of untruth, prejudice and their concomitant, war.” She produced one more book in 1951, Further English Voyages to Spanish America, 1583–1594, published by the Hakluyt Society. Of honors there were many more, and in 1953 she served as president of the Society of Woman Geographers. She died on 6 April 1972 in New York.

Lamb wrote that Wright left “indelible traces on the path of scholarship.” Indeed, her work opened countless research avenues for future historians, and references to her publications pepper the footnotes and bibliographies of numerous modern books and articles on Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico history. Her vast achievements are all the more remarkable considering the highly conservative male-dominated cultures in which she had to operate. Late in life, Wright quipped that at Seville she became, “the boon companion of every pirate who sailed the Spanish Main,” and she is still regarded as such by anyone moved to study that fantastical realm today.

John S. Sledge recently retired from the Mobile Historic Development Commission after thirty-eight years of service. He is currently the maritime historian-in-residence at the National Maritime Museum of the Gulf of Mexico, and a member of the National Book Critics Circle. He is the author of eight books, including The Mobile River, The Gulf of Mexico: A Maritime History, and Mobile and Havana: Sisters Across the Gulf, an excerpt of which was published in Sea History 185.