This article originally appeared in Sea History.

They called it the Pastry War. But instead of a charming pâtisserie as the setting, delighted children and bemused adults as the participants, and flying chouquettes, croissants, éclairs, and macrons as the projectiles, it featured a gray harbor fort, serious military men, steam warships, and exploding artillery shells. It took place at Veracruz, Mexico, in 1838 and, though little known today, is significant for auguring a new era of naval warfare.

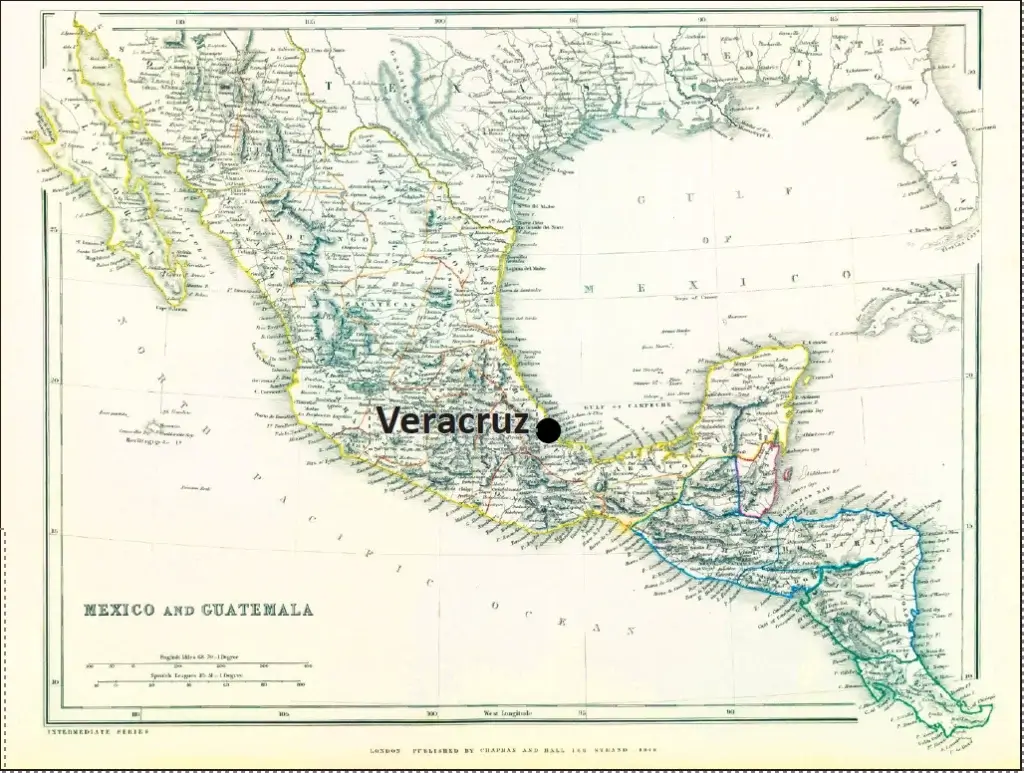

Ten years in the making, the conflict stemmed from a Mexico City street riot between rival political factions. Mexico had achieved independence in 1821 but suffered continual political intrigue and frequent leadership changes in the years afterwards. During one such power scuffle, unruly soldiers thronged a French-owned pâtisserie, gobbled up 800 pesos’ worth of treats without paying, and generally wrecked the premises before leaving. The shop’s owner, one Monsieur Remontel, did not take kindly to this outrage and claimed 60 thousand pesos in damages. This was an astronomical sum at the time, and the Mexican government haughtily rejected his claim. Not easily deterred, Remontel pressed his case for years, and by 1838 he had taken it to the French government. Rather than dismiss it as a trivial distraction, King Louis-Phillipe saw it as an opportunity to call in Mexican debts, as well as to recoup the losses of other French citizens in the unrest, all to the tune of 600 thousand pesos. Unsurprisingly, the sitting Mexican president, Anastasio Bustamante, refused, leading Louis-Phillipe to send his navy to Veracruz to coerce payment. Veracruz is located roughly halfway down Mexico’s long, gracefully curving Gulf Coast with the snowy summit of Mount Orizaba providing a dramatic background. During the early nineteenth century, it was a city of considerable importance, with flourishing trade contacts throughout the Atlantic basin. Founded by Hernán Cortés in 1519, by the early nineteenth century it boasted a population of roughly 10,000 souls. It was a vibrant city but had a fearsome reputation for northers (strong wintertime fronts that regularly scattered shipping) and disease, particularly yellow fever, graphically referred to locally as el vomito. Nonetheless, visitors were generally impressed. Seven years before the Pastry War, a British barrister named Henry Tudor described the city’s appearance from the water as “remarkably pretty; exhibiting a showy aspect of churches, with their various spires and towers—of white-washed houses with their terraced roofs—and surrounded entirely with fortified walls.” History had demonstrated the efficacy of those walls more than once, including against sixteenth-century pirate attacks and an 1825 Spanish siege. Even more important than the wall was the brooding harbor fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, situated on an emergent coral reef half a mile offshore and facing northeast, or seaward. It was originally constructed in 1535 and improved throughout the eighteenth century.

By the mid-1830s, it consisted of a rectangular parade ground surrounded by fifteen-foot-thick coral curtain walls and sharply angled corner bastions with a brick lighthouse, a cavalier (an interior fortress raised to fire over the main parapet), and a demilune on the seaward side with flanking redoubts and moats. The armament included 187 guns and the garrison, 1,200 men. Contemporaries considered it well-nigh impregnable, the “Gibraltar of America.” While that had been true theretofore, troubling disadvantages were evident to knowledge-able observers. The coral block walls were not likely to stand up to a sustained pounding by modern shell guns, there were almost no interior casemates to provide lateral protection to the gun crews, the artillery was small caliber and badly mounted, the gunpowder was inferior, and the men were poorly trained conscripts.

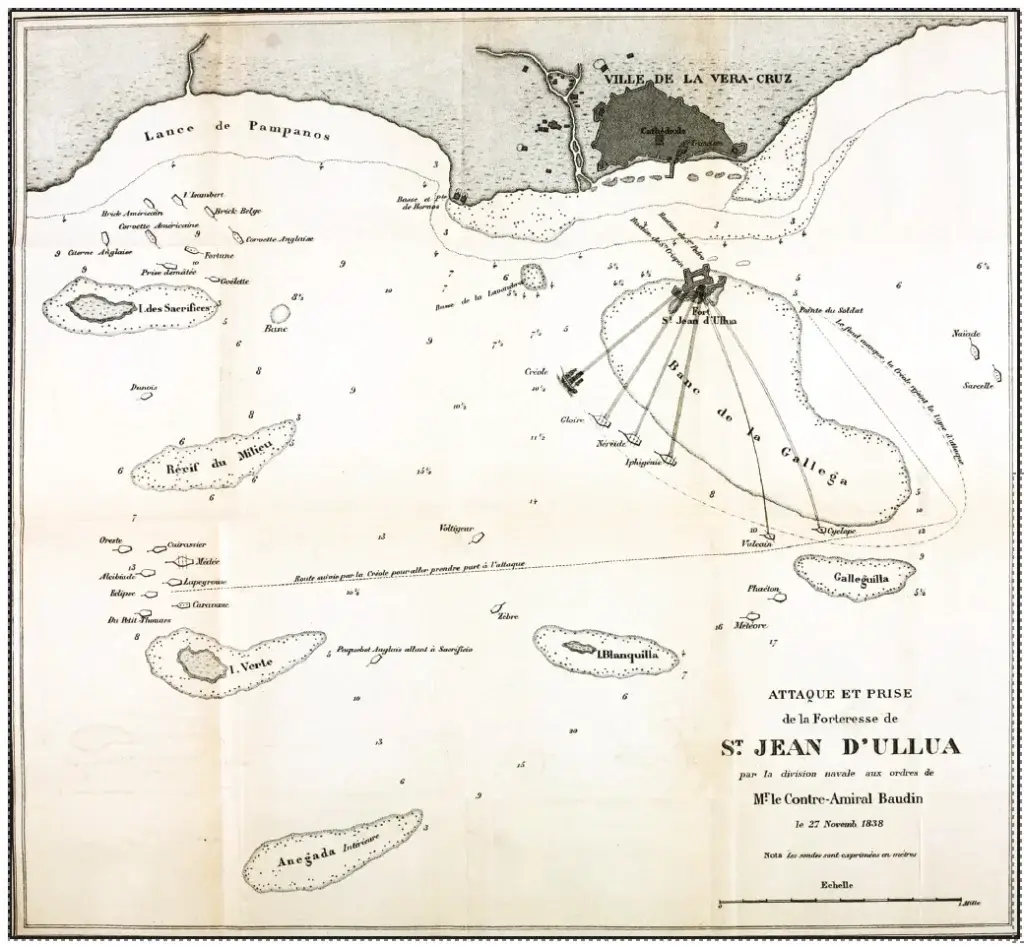

The French fleet arrived in March, and the King’s Minister to Mexico, Baron Antoine-Louis Deffaudis, formally presented a list of demands to Bustamante that included payment of the debt by 15 April, the release of any French citizens held in Mexican jails, and the removal of “certain offending officials.” Bustamante labeled the demands “un verdadero libelo” (a true libel) and put his trust in el vomito and strong northers to drive away the enemy. In response, the French suspended diplo-matic relations and blockaded Veracruz. Just as Bustamante had hoped, disease and storm afflicted the fleet, but it did not withdraw, and the standoff remained unresolved into the fall. Eager to force a conclusion, Louis-Phillipe sent more ships under Rear Admiral Charles Baudin. By October, two dozen French vessels were holding station offshore, including transports loaded with 4,000 troops; three frigates armed with fearsome Paixhans shell guns; two bomb ketches; a sloop-of-war; two steamers, the Phaeton and the Météor, each boasting 160 horsepower engines; and a handsome twenty-four-gun corvette named La Créole under the command of the King’s son, twenty-year-old François d’Orléans, Prince of Joinville. Since the Mexicans were determined not to fire first, Baudin took the opportunity to dispatch crews in long-boats to take soundings right up to the walls of San Juan de Ulúa.

On hand to protect American interests was USS Erie, a trim sloop-of-war com-manded by Captain David Glasgow Far-ragut. Before the hostilities started, the young American officer took the opportu-nity to visit the French admiral’s 52-gun flagship Néréide. He was impressed by Baudin, a balding, 53-year-old, one-armed fighter who had seen service in the Napoleonic Wars. Baudin, a master seaman and strategist, openly shared his plans. After an hour in his company, Farragut opined that he would have been a “rara avis in any navy.” He admired the admiral’s battle-ready decks, everything shipshape and squared away. He took particular interest in the 32-pounder guns equipped with new percussion locks, “no spring, no machinery, in fact, nothing that can become deranged” and expected the coming contest to be one-sided and short.

The French had set 27 November as their new deadline, after which “war or peace would immediately follow.” Guessing that diplomacy had run its course, Farragut had his blue jackets embark all US citizens and their valuables. As expected, Bustamante was in no mood to concede anything to Baudin. On the appointed day Farragut anchored safely off to one side and watched as the Phaeton and Météor towed the frigates into the most advantageous positions.

Steam technology was yet young, but, applied to naval warfare, it provided even better evidence than the new percussion locks that the old ways were doomed. “Everything was done by them,” Farragut wrote of the steamers. “The day was calm, or nearly so, and the ships had no sails to manage. As soon as the anchor was let go, they were ready for action.” Slim, bearded, and eager to “share in the fun,” the Prince of Joinville begged Baudin permission for La Créole to join the frigates. This was a brash request, as the corvette’s guns were, in Joinville’s own words, “mere children’s toys.” Permission was denied, and he was ordered to simply observe. Still refusing to open hostilities, the Mexicans waited behind their coral walls. “At precisely 2:30pm,” Farragut wrote, “the Admiral’s ship fired the first gun, and immediately the firing became general.” Bright tongues of flame leapt from gun muzzles, and heavy smoke enveloped the ships. To his great joy, Joinville was granted permission to join the bombardment; he immediately got underway, gliding alongside the thundering frigates and tak-ing position in a line at their head. Despite his small battery, Joinville relished being in the thick of the action. Farragut wrote that the “Prince had the hottest berth, but stood his ground like a man, occasionally wearing ship to bring a fresh broadside to bear.” The fort’s shots were ragged, but Joinville could see the frigate Iphigénie taking hits. “Every minute or two I saw splinters of wood flying into the air, cut out by the shot striking her,” he wrote. Fortunately, Iphigénie’s damage was slight because of the Mexicans’ bad powder and small guns. By contrast, the fort suffered terribly. Farragut was astonished to see the French shells punch holes a foot deep into the coral walls and then explode, “tearing out great masses of stone, and in some instances rending the wall from base to top.”

Inside the fort, gun carriages were upended, men were hit by humming fragments, the powder magazine exploded, and the square tower and its defenders were blasted to smithereens. According to an account later published in the New Orleans Bee, the magazine blew “with so much violence, that the decks of several of the French vessels at the distance of more than a mile, were strewed with their fragments.” It was more than soft coral, human flesh, or weak will could withstand. By sunset, the fort was a smoking ruin, and the Mexican garrison capitulated. Joinville toured the scene the next day and wrote, “A horrible smell rose from the numerous corpses buried everywhere under the rubbish.” Over 200 Mexicans were dead. The surviving members of the garrison tied weights to their deceased comrades and sank them in the harbor. Unfortunately, they did a sloppy job, and in a ghastly coda to the whole affair, Farragut wrote that the deceased “were seen floating about in all directions.” French losses were trivial by contrast. Baudin cursed “the folly” of his brave opponents’ leaders for putting them in such an impossible position.

The French occupied the shattered fort and allowed the defenders to withdraw, their honor intact. The overall Mexican commander at Veracruz then decided to parlay with Baudin, hoping to avoid a bloody siege. He readily accepted conditions that included letting the French pro-vision from the city and sending all but 1,000 of his soldiers at least ten miles out of town. Predictably, this news riled the capital. The central government under Bustamante made a formal declaration of Inside the fort, gun carriages were upended, men were hit by humming fragments, the powder magazine exploded, and the square tower and its defenders were blasted to smithereens. According to an account later published in the New Orleans Bee, the magazine blew “with so much violence, that the decks of several of the French vessels at the distance of more than a mile, were strewed with their fragments.” It was more than soft coral, human flesh, or weak will could withstand. By sunset, the fort was a smoking ruin, and the Mexican garrison capitulated. Joinville toured the scene the next day and wrote, “A horrible smell rose from the numerous corpses buried everywhere under the rubbish.” Over 200 Mexicans were dead. The surviving members of the garrison tied weights to their deceased comrades and sank them in the harbor. Unfortunately, they did a sloppy job, and in a ghastly coda to the whole affair, Farragut wrote that the deceased “were seen floating about in all directions.” French losses were trivial by contrast. Baudin cursed “the folly” of his brave opponents’ leaders for putting them in such an impossible position.

The French occupied the shattered fort and allowed the defenders to withdraw, their honor intact. The overall Mexican commander at Veracruz then decided to parlay with Baudin, hoping to avoid a bloody siege. He readily accepted conditions that included letting the French provision from the city and sending all but 1,000 of his soldiers at least ten miles out of town. Predictably, this news riled the capital. The central government under Bustamante made a formal declaration of war and funneled more troops toward the coast. It was at this turbulent moment that General Antonio Lopéz de Santa Anna reinserted himself into national affairs, promising to defend the city.

If ever there was a genius at exploiting the main chance, it was Santa Anna. He was 44 years old, tall, darkly handsome, and brave—though a flawed military strategist. Ever since his crushing defeat two years earlier by Sam Houston at San Ja-cinto, he had been keeping a low profile at his nearby villa. The Pastry War provided him the ideal opportunity to rescue his beloved nation from humiliation and defeat. He thus obtained the government’s blessing and appeared in Veracruz’s plaza announcing the declaration of war and his intention of throwing the French into the sea. Farragut and several of his officers paid the General a visit on 29 November and were cordially received. Santa Anna assured them that American citizens would be respected. He also appealed to their shared geographic interests, asking them to tell President Martin Van Buren “that we are all one family, and must be united against Europeans obtaining a foothold on this continent.” This unusual play on hemispheric solidarity was vintage Santa Anna, as were his parting comments that the recent surrender was an outrage and he would “die rather than yield one point for which they had contended.”

Exasperated by this development, Baudin declared that he would not wage war on innocent civilians because of their government’s stupidity. To avoid a messy siege, he concocted a plan to gut Santa Anna’s preparations before they went any further. On the foggy morning of 5 December, three French infantry divisions landed on the city’s wide waterfront—one to the south, one at the center, and one to the north. Among the troops in the center column was Joinville, in direct command of sixty men. French sappers laid black powder charges under the gates and blew them open. “Forward! God save the King!” shouted Joinville as the French surged into the city and made for Santa Anna’s headquarters. “There wasn’t a cat in the streets,” Joinville later testified. But the Mexicans were waiting for them, hidden in houses and perched among the rooftops. French soldiers began falling as resistance mounted. Ignoring the “musketry fire crackling from every window like a great set piece of fireworks,” Joinville directed his men through the alleyways towards the governor’s house. Once there, they “hurled into a room full of smoke and Mexican soldiers.”

Joinville captured a general, but Santa Anna escaped “in his shirt and trousers.” The French forces continued to push inland, and their losses increased. Alarmed by his casualties and not interested in capturing the city, Baudin ordered a withdrawal. True to form, Santa Anna seized the moment when French retreat was certain to sally forth with several hundred men, parading in front of them on a pranc-ng white charger. To all appearances he intended to harry the enemy to the water’s edge and apprehend Baudin himself. The French responded by hauling up a small field piece, “loaded to the muzzle with grape and canister” according to Farragut, that raked the Mexican line. Santa Anna was among the wounded, hit in the left leg, which had to be amputated shortly thereafter. Santa Anna was nothing if not resourceful, however, and in inimitable style he parlayed his misfortune into advantage. He was now viewed as the savior of Vera-cruz, one who had given a leg in its defense, and he once again ascended to the presidency. The war ended when the British, impatient with the blockade’s disruptions, sent a small fleet to help broker a treaty. Santa Anna’s loud pronunciamentos to the contrary, the Mexicans paid the French every peso owed. The Pastry War was over, with Veracruz once again open to commerce. Santa Anna was a hero of Mexico, and young Capt. Farragut sailed away mull-ing the lessons he had learned watching steamships and shell guns pummel an old harbor fort—lessons that in the fullness of time he would apply at New Orleans and Mobile Bay.

This article was adapted from John S. Sledge’s latest book, The Gulf of Mexico: A Maritime History, published by the University of South Carolina Press. Sledge is senior architectural historian for the Mobile Historic Development Commission and a member of the National Book Critics Circle. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history and Spanish from Auburn University and a master’s in historic preservation from Middle Tennessee State University. Sledge is the author of six previous books, including Southern Bound: A Gulf Coast Journalist on Books, Writers, and Literary Pilgrimages of the Heart, The Mobile River, and These Rugged Days: Alabama in the Civil War.